Classic Films of Enduring Love

Love — romantic love — has been a central theme, maybe the central theme, of the Modern age’s most popular art-form: the movies. And why ever not? One of the revelations of a life lived long enough is that the old truism really is true: Love really does make the world go round.

Love is a central theme of Literature, too. But a love story on the page depends entirely on the images conjured in the reader’s imagination of the central characters. With images cast on a movie screen, we have a common denominator — two actors, living and breathing and falling in love — and we can, unmediated and immediately, relate. Especially in times like our own, so chaotic and violent and unpredictable and cynical — and to our point, so thin on love — films of enduring love signify all the more, steadying like an anchor, brightening a gray landscape, reinforcing a verity out of so many lost (truth, honor, justice).

For me, the films of enduring love that endure have two defining qualities: first, an emphasis on relating — two people bringing their universes to the table where they mesh (or not), where they learn, laugh, fall in love. Spare me the gauzy atmosphere or acres of skin; give me the relating. Second, the woman character must be substantive: one who acts, not just reacts. Thus Alfred Hitchcock’s “Notorious” doesn’t qualify: While any film featuring Cary Grant normally does it for me, and Grant and Ingrid Bergman do convey enduring love at the end, the Alicia character is Fortune’s plaything (in the interim she marries a Nazi). Character counts for women, too.

So, my classic films of enduring love. To become classic, a film must stand the test of time, thus most are from the 1930s, ’40s, ’50s. Being classic, most will be familiar, but it’s their familiarity that repays in dark times (my spoilers aside). In these films, you come to know the characters so well and care for them so much, that they feel like family; equally, you feel the durability of their love. As I am fortunate to enjoy enduring love myself, I give this category highest priority.

Enduring love that does not work out (in marriage) — but nourishes forever

“CASABLANCA” (dir. Michael Curtiz, 1942)

Any list of enduring love must begin with “Casablanca”: Rick and Ilsa, played by Humphrey Bogart and Ingrid Bergman (pictured at top), are perhaps the world’s most famous lovers, up there with Romeo and Juliet. This film is my all-time favorite, for many reasons: because Rick eventually overcomes his cynicism to rejoin the fight, World War II; because his Café Americaine is filled with refugees yearning to make their way to America, then seen as a moral beacon; because of vivid supporting roles. And because of Rick and Ilsa. Earlier, when Rick and Ilsa met in Paris, Ilsa believed her freedom-fighter husband Viktor Laszlo had been killed by the Nazis. When she learns he’s alive, she does the right thing: She returns to her husband, leaving Rick embittered, his state of mind in Casablanca when Ilsa and Viktor (Paul Henreid) — in one of cinema’s more outrageous coincidences — walk into his gin join. While Ilsa appears ready to leave Viktor for Rick, Rick does the right thing in turn: He gets them the visas to get out of Casablanca, while recapturing for himself and Ilsa what they once had: “We’ll always have Paris.” The ethics of love, the physics of love (gaining while losing) — this classic has it all. (“Casablanca” won Oscars for best picture and director.)

“ROMAN HOLIDAY” (dir. William Wyler, 1953)

This bittersweet film charms, then breaks your heart. The sweet part: A royal princess named Ann (Audrey Hepburn), making a state visit to Rome, breaks free from Duty and heads out for adventure. She finds it when she crosses paths with an American reporter, Joe Bradley (Gregory Peck). At first he’s focused on exploiting his scoop (lost princess discovered), but then he parks it as he begins falling for her and joins her in the adventure. A close call with her security detail, though, brings home the inexorability of their situation: A princess can’t stay AWOL forever. Finally, the bitter part: Ann must return to her Duty. But first, they share one of the best farewell kisses in all cinema. Peck and Hepburn are superb, Peck was so impressed with the newbie actress he predicted big things for her; indeed Hepburn won the best actress Oscar for the role. Eddie Albert is droll as Joe’s photographer pal, who commemorates their key moments. Director William Wyler excels in conveying real people in real drama. The reality here: Not every romance works out, but for this pair, they’ll always have Rome. I adore this film (and have my VCR cued to that farewell kiss.)

“BRIEF ENCOUNTER” (dir. David Lean, 1945)

Another bittersweet film, one set a bit later in the characters’ lives: at midlife. Told in retrospect by Laura (Celia Johnson) — with all the compacted emotion of a suburban housewife trying desperately not to acknowledge her growing feelings for a man other than her kindly husband — she recounts her brief but life-altering encounter with Alec (Trevor Howard), a doctor, also married. It all started in a station on the London trainline, when he removed a cinder from her eye. These two soulful people, warming to each other, arrange jaunts from the station: a movie, a boating excursion. What they hadn’t arranged for: love. The film takes on new depth when Alec states reality: “You know what’s happened, don’t you,” and Laura does not duck: “Yes, I do.” Then she fights harder than ever to resist, unsuccessfully. Their reckoning is as shameful for these respectable people as she feared; their parting, shattering. While this film is often sent up for its melodrama and pulsing Rachmaninoff theme (Nichols and May do a wicked bit on it), I cherish the honesty. In any serious relationship, there comes a moment of recognition: What do we have here, what do we do with it? In these lying times, I love Alec and Laura’s honesty.

“IN THE MOOD FOR LOVE” (dir. Wong Kar-wei, 2001)

Set in 1960s Hong Kong, this film seems a teaser to an affair — when will these attractive people, married to others, fall into each other’s arms? But it becomes so much more: a paean to moral strength: When they learn their spouses are having an affair — with each other(!) — their struggle deepens. Determined not to become “cheaters” like “them,” the film charts their growing desire for each other. Holding the line, she observes, is “more complicated” than any marriage; when a coworker urges he “go for it,” he replies, “I’m not like you.” She is Mrs. Chan (Maggie Cheung), a shipping executive’s secretary; he is Mr. Chow (Tony Leung), a journalist; they first meet in tight quarters, living in rooms rented out by apartment-holders. Sliding by each other daily, their attraction takes; finally they dine out, leading to more dinners, deep relating. Transgression is rife — she covers for her boss’ affairs with lies to his wife. But, at the end of their day, though they part, fidelity rewards, achingly. This superbly acted film is amplified by a Greek chorus, from Mrs. Chan’s landlady who worries for her lonely renter, to the household cook who senses something afoot, because Mrs. Chan “always goes out dressed so nice.” This filmmaker is unafraid to go slow, the better to hone character, consecrate memory. And the soundtrack: The haunting theme, a slow waltz on cello, melds with Chinese opera, Mandarin pop, and (no kidding) Nat King Cole. Unforgettable, truly.

(“Now, Voyager,” with Bette Davis and Paul Henreid, which I reviewed earlier, ends with the settlement line all such romances must end in: “Let’s not ask for the moon, we have the stars.”)

Enduring love that does work out — in marriage

“LOVE AFFAIR” (dir. Leo McCarey, 1939)

This is a story of a shipboard romance that, after terrible struggle, ends triumphantly. Terry (Irene Dunne), a singer, and Michel (Charles Boyer), ladies’ man and wannabe artist, both in relationships with others, meet on a transatlantic cruise and “spark.” At a port visit enroute to New York, they make a pilgrimage to his beloved grandmother, a widow who senses their relationship is serious, and approves. In New York harbor, they must take stock: They agree that, if in one year they are free, they will meet again, at the top of the Empire State building. A year goes by; Terry, unaligned, heads for the Empire State building and, because she’s looking upward, walks into traffic, with devastating consequences: She may never walk again. Showing no self-pity, she shifts to teaching music to children. Michel, desolate at being stood up at their reunion, gets serious about painting. This film is too well-known to be ruined by this synopsis. What I like: the complementarity enabling enduring love — if he can paint, surely she can walk again. A later remake featured Deborah Kerr and Cary Grant, directed by the same director, recreated beat for beat. This film got sent up as a woman’s weepie in “Sleepless in Seattle,” when Tom Hanks and pal play-weep over “The Dirty Dozen.” Laugh, gentlemen: This story is classic.

“THE SHOP AROUND THE CORNER” (dir. Ernst Lubitsch, 1940)

In this love story starting out as a mismatch, much labor is required to get to the happy ending. Alfred Kralik (James Stewart) and Klara Novak (Margaret Sullavan), clerks in a Budapest leather-goods shop, exemplify employee relations at their worst. Kralik is frustrated at his lack of advancement, feeling unappreciated by the owner (Frank Morgan), who suspects Kralik of being his wife’s lover. New hire Klara disputes Kralik, her senior, having her own ideas about salesmanship. They really don’t like each other — except, really, they do: They are, unbeknownst to them, each other’s romantic pen-pal — the “Dear Friend” to whom they pour out their highest thoughts on Life and Love. Kralik is first to learn the identity of his “Dear Friend” — after his shock, he’s intrigued — but he’s not above messing with Klara about her ideal beau, talking him down to elevate himself. Things stay prickly until the big reveal. Sullavan, never my favorite, plays prickly well; so does Stewart, usually cast as more congenial. This film is not my heart’s favorite, either, but I chose it because: Love sometimes takes work, with someone not originally on your short list. As Fats Waller said, “One never knows, do one?”

“LAURA” (dir. Otto Preminger, 1944)

Usually considered a thriller, this film also works, terrifically, as a love story. Named after the beautiful woman who’s presumed murdered and whose portrait hanging in her apartment mesmerizes the detective working her case, the film starts as a police procedural, with Mark McPherson (Dana Andrews) questioning everyone in Laura’s circle. When Laura herself (Gene Tierney) makes her entrance — she’s been away, unaware of her own demise — the film is half over, but amazing distance is made between then and The End, in just three scenes she and McPherson have together. Once he recovers (“You’re alive!”), he asks, point-blank, if she’s decided to marry Shelby Carpenter (Vincent Price), her fiancé and by now his rival — “I want the truth”; when she says No, a smile flickers on his poker face: In one pass, he got what a year of dating takes. By their second scene, Laura commits to McPherson’s daring methods; by the third, they kiss, with Laura leaning in. (A detective’s directness helps: saves on “fencing.”) Still, the killer lurks out there…. The cast is superb, notably Clifton Webb as columnist Waldo Lydecker, who senses early McPherson’s infatuation with the woman he too loves: He’ll be the first cop “to fall in love with a corpse.” Will their love endure? The chemistry between the two leads guarantees it. (Full movie here.)

“MOONSTRUCK” (dir. Norman Jewison, 1987)

This tale of a woman engaged to the wrong brother, and who takes the whole film to see what the viewer sees all along, is a hoot, with one of the best final sequences in all film. Loretta (Cher), who lives with her extended Italian family (grandpa included) and works as bookkeeper in her uncle’s store, has been in a long-term engagement with Johnny (Danny Aiello), poster boy of a man incapable of committing. How long-term is this engagement? Loretta is starting to go gray, yet as the film opens, Johnny finds yet another excuse: His mother in Sicily is dying, he must go to her. Meanwhile, his brother Ronny (Nicolas Cage) meets Loretta and, very soon, is more than willing to commit. Both tempestuous types, Loretta and Ronny are a match: Cher and Cage’s lack of affect make their tempestuous all the funnier (Cher won the best actress Oscar). The final sequence opens when Johnny returns from Italy, Ronny’s there with Loretta; everything gets sorted in the Castorini kitchen, hilariously. A subplot gets sorted, too: Loretta’s father Cosmo (Vincent Gardenia), ensnared in a midlife affair, comes home, finally, to her mother Rose (Olympia Dukakis). My VCR is cued to this finale, an ode to enduring love, generational class. (Playwright John Patrick Shanley won the Oscar for best original screenplay.)

(My reviews of other films of “love triumphant”: “Spellbound,” “Ninotchka,” “It Happened One Night,” in which Clark Gable makes “love triumphant” the test.)

Enduring love in marriage — tested severely

“RANDOM HARVEST” (dir. Mervyn LeRoy, 1942)

When I think of enduring love, I think first of this film: about a love that endures through shell-shock, death, Time. It is the end of World War I. Paula (Greer Garson), a singer in a traveling troupe, meets a shell-shocked soldier, “Smithy” (Ronald Colman), escapee from an asylum. He seems normal; they fall in love, marry, have a child; all is blissful. But Smithy, in town to apply for a journalist job, is hit by a cab — and loses all memory of Paula and the baby, while regaining memory of his early life: He is Charles Rainier, scion of a great manufacturing family. He takes over the faltering firm, revives it; Paula learns of him, years later, from a news article hailing him as “Industrial Prince of England.” She reenters his life, coming (to our surprise) through his office door — as his secretary; sadly, he has not recognized her. She makes herself invaluable to him, in the business, in his successful run for Parliament. He inquires into her past, learns she had a child who died. They marry, pro forma for a politician, but she is miserable: so close and yet so far. Restoration involves the key to the cottage of their long-ago life. This film — which won Oscars for best picture and actor for Colman; Garson won that year for “Mrs. Miniver” — lives on: as testament to enduring love and the enduring faith — Paula’s — in it, come whatever may.

“WATCH ON THE RHINE” (dir. Herman Shumin, 1943)

Casting about for a film portraying a married couple united in recognizing the peril of their times — fascism in Europe — and the sacrifice they make to stop it, I think of this film that began as a stage play, by Lillian Hellman. Politically, it resonates today with Americans alarmed at the assault on our own democracy: Fascist or not, it comes from forces within, thus requires counter-forces also from within — political astuteness and unity. Bette Davis and Paul Lukas play that counter-force, powerfully (Lukas won the best actor Oscar). Made as World War II was raging and set in April 1940, just months before much of Europe would fall to the Nazis, this film is about those few — ordinary people, “not prophets” — who saw the “mighty tragedy” coming. Kurt, a German and member of the anti-fascist underground, and Sarah, his American wife, have escaped Europe with their three children, seeking refuge at her mother’s home in Virginia. So much of their fight against fascism chimes today: the growing violence, the “sick” cruelty, the mindless “shabby kind” who tolerate, even profit from chaos. Americans, Sarah notes, “don’t know what it is to fight” this evil: “Unfortunately you’ll have to learn” (Europe is relearning, with Putin’s assault on Ukraine). So united are they, it is Sarah who announces Kurt must go back (to save a comrade who saved him), knowing he’ll not likely return. I love the moment at the piano, when Sarah must tell Kurt some vital news: Shocked, he stops playing, and she picks up where he left off. Love enduring.

“AN IDEAL HUSBAND” (dir. Alexander Korda, 1947)

Lady Chiltern married her husband, and loves him more than ever, for his high moral character: To her, Sir Robert is the ideal husband. He in turn worships her. Such marriage can withstand anything — but not dishonor, and here it looms. Based on Oscar Wilde’s play and set in 1895 London — “When Britain ruled the wave and held the purse / Here was the center of the universe” — the story’s ethos mirrors our own: an ethos driven by money and success. As Sir Robert (Hugh Williams) notes: “Every man of ambition has to fight his century with his own weapon. This century worships wealth.” He, well-born but poor, needed wealth to succeed in politics, and he has: He’s under-secretary of state, a member of Parliament, touted for the cabinet. But, his gains are ill-gotten: At 22, he passed inside information on the Suez Canal and profited big-time. Now comes the opportunist Mrs. Cheveley (Paulette Goddard), who has his incriminating letter, in exchange for which she demands he pledge government support for another canal scheme in which she’s invested. Lady Chiltern (Diana Wynyard), learning all this, confronts her husband, lovingly but directly: “Is there in your life any secret disgrace?” Multiple complications ensue, pushing them to break-point. Will this ideal marriage survive? Wildean heart and wit ensure enduring love. (A 1999 remake stars Cate Blanchett, Jeremy Northam, Julianne Moore.)

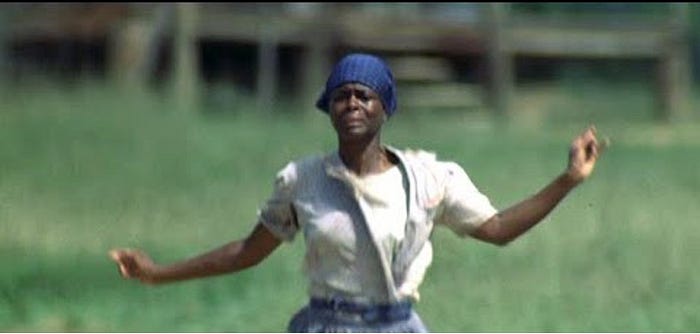

“SOUNDER” (dir. Martin Ritt, 1972)

Nathan and Rebecca’s enduring love enables them to withstand poverty — they are sharecroppers in Louisiana during the Great Depression — and racism, America’s bane. But while love buoys them and their three children, it doesn’t feed them. When Rebecca (Cicely Tyson) assures Nathan (Paul Winfield) they’ve survived hard times before, he erupts: They work themselves to death, but “we can’t eat even when croppin’ time is done.” Next morning, though, there’s meat cooking: Nathan raided a white farmer’s smokehouse. When he’s arrested, Sounder, the family dog, bounding after him, is shot. This is tragedy enough to sunder anyone, but Rebecca steps up: She and the children plant next year’s crop, keep the farm going; and she continues taking in white folks’ laundry. When the sheriff denies her to see Nathan (no women), she daringly notes his “low-life job.” When oldest son David visits, Nathan says he’d like to “knock down these walls so’s I could get my arms around your mama.” Once Nathan is sent to a labor camp, the film focuses on David, as he treks to see his father, with Sounder now healed. Enroute, David discovers a Black school: his future. But when Nathan is released early due to injury, the film refocuses on the marriage: Who ever can forget the famous scene of Rebecca running down that long hill to embrace her Nathan Lee? (Tyson told Turner Classic Movies the director wanted many more takes of that scene: “Whaaat?”) Both Tyson and Winfield received Oscar nominations for their loving portrayals.

(My reviews of other films of enduring marriage: “Mrs. Miniver” and “It’s a Wonderful Life.”)

Marriages in repair — and restored, eventually, to enduring love

“WOMAN OF THE YEAR” (dir. George Stevens, 1942)

Marital trouble in this dramedy is rather easily resolved, and might not qualify as a true test, but I cannot imagine a discussion of enduring love without a vehicle featuring Katharine Hepburn, my early favorite actress, and Spencer Tracy. Tess Harding and Sam Craig work for the same newspaper, she as foreign affairs columnist, he as sports writer. The falling-in-love part is fun: He takes her to her first baseball game (she gets bamboozled); they get serious in a bar; they get married. But Tess, recipient of “woman of the year” awards for successfully innovating the role of career woman, is less successful at the work-balance thing that women are required to handle (and still are): When they adopt a Greek orphan, Tess treats him more as pet than responsibility, a moral short-changing Sam finds deeply disturbing. After more short-changing by his ambitious wife, Sam leaves. Tess comes to a new understanding of what makes love endure — mutual commitment, total — when she stands as witness at her widowed father’s marriage to Ellen, the woman Tess always considered her “woman of the year.” How Tess wins Sam back — cooking breakfast for him — is, yes, retrograde, as is the male dominance thing. But recommitment is taking place in that kitchen, and it’s done with wit: Tess, inept cook, is doing her darnedest.

“VACATION FROM MARRIAGE” (dir. Alexander Korda, 1945)

This little-known gem should be better known, because it portrays a problem afflicting many marriages after a certain point, say seven years: The spouses are bored with each other. More, they are bored with their lives and routines, in pre-World War II London. But war, notably one that’s the life-and-death geopolitical struggle this war was, confers significance on the lives of those who fight in it. That is the case for Robert (Robert Donat), a bookkeeper, when he’s drafted into the Royal Navy, but also for Cathy (Deborah Kerr), who signs up for the Women’s Royal Naval Service. Both find new utility in their wartime roles, new humanity in their comrades; Cathy’s comrade Dizzy (Glynis Johns) introduces her to lipstick, glamour. Both have fleeting infatuations, Robert pursuing the nurse (Ann Todd) who tends him after his hands are burned in battle, while Cathy is pursued by Dizzy’s cousin. Robert and Cathy stay in touch with letters, but nothing prepares them for life together again: They are new people, Robert a hero. Reunion goes bumpily at first (very), but eventually…. Strange to treat war as “vacation,” but it serves as the recommitment ceremony these two needed. (The screenplay won the Oscar for best story.)

“A LETTER TO THREE WIVES” (dir. Joseph L. Mankiewicz, 1949)

More threatening than ambition or boredom, another woman figures in this drama nominated for the best picture Oscar (it won for best screenplay and directing). At the outset, the wives of three couples, friends who socialize together, receive a letter from Addie Ross, the other woman whom all their husbands admire, maybe even loved at one time. In it, she informs them that, by that evening, they will learn which of their husbands she ran away with. The day, then, becomes a trust exercise as all three, together chaperoning a children’s cruise, ruminate over their marriages, reexamine the chinks therein, and wonder: Is it my husband? Jeanne Crain plays the newest member of the circle and the least confident of her husband (Jeffrey Lynn). Ann Sothern, playing a woman trying to make a career in advertising, seems surer of her husband, a teacher played by Kirk Douglas. The most combative marriage seems the likely target: A wealthy businessman, played by Paul Douglas, fears his wife, played by Linda Darnell, married him for his wealth, not love. This film comes at marriage from the inside — where marriages live or die — and examines the greatest threat to that emotional core: the marriage-annihilating threat posed by another woman or of course another man. The superb ensemble acting here underscores what all want: enduring love, enduring marriage.

“JOURNEY TO ITALY” (dir. Roberto Rossellini, 1955)

In this film, the marriage is nearly broken. We meet Katherine (Ingrid Bergman) and Alex (George Sanders), an English couple on the road to Italy, to sell a villa near Naples. Their first lines are metaphoric: Alex asks Katharine (who’s driving), “Where are we?” Her response: “Oh I don’t know exactly.” They are at sea — arguing, snide, hurtful. By the time they get to Naples, they acknowledge: After eight years of marriage, they are “strangers.” With their full life in London, things seemed “so perfect,” but now, alone together…. Jealousy does its work: He’s too attentive to other women; she recalls, again and again, a poet she knew before they married. They churn their old complaints: He feels misunderstood, she feels demoted from wife to hostess. He goes off to Capri to “have fun” (and can’t); she visits museums and, in her heightened state — she admits, out loud, “I hate him!” — she becomes more attuned to ancient truths about love and life. But when he returns, they are at it again and have it out: They will divorce. But first, their host insists, they must visit Pompeii: to see newly discovered human remains. The sight of a man and woman, together, in the moment of their death, impinges. History’s deep perspective will restore them, but they must reform: “Why do we torture each other?” “Because you hurt me, I hurt you.” Finalmente, basta.

(My reviews of other films of marriage in repair: “The Philadelphia Story,” “The Awful Truth,” and “Dodsworth.”)

As for enduring love enduring after death: The nurse in “Vacation from Marriage” remembers her late husband thus — “He had a mind like a lamp.” That love will carry her onward.

Again, in these chaotic time, tales of enduring love are steadying. Again, the spoilers should not spoil the overarching truth: Love of the enduring kind is its own high achievement, occupies its own special realm. There are many maps to enduring love; these films chart a few. Savor them, savor it: love enduring.

My other film commentary: on women film heroes, classic political films, classic films of human drama, classic foreign films of human drama, classic screwball comedy, classic films of character and courage, light moments from film and TV.